Intergovernmentalism & Liberal Intergovernmentalism

If (neo)functionalism represents IR liberalism in the European Integration debate, (liberal) intergovernmentalism certainly constitutes its realist counterpart. But it would be a mistake to think that European Integration intergovernmentalists were ever as hard-nosed as proper realists, with their near-exclusive focus on the relative position of states in the international balance of power. In fact, intergovernmentalists always factored domestic forces into their equations. Their objective was never to understand European Integration as a mere temporary alliance directed at (military) security, but to bring the nation-state back to the centre of its analysis.

The Nation State at the centre of the debate “Give us a break with your nation-states”. Cartoon by Wolfgang Ammer.

European Integration intergovernmentalism was born out of a critique of neo-functionalism. Focusing primarily on the attitudes taken by French President Charles De Gaulle in the 1960s, Stanley Hoffmann argued that integration might work very well in the realm of low politics (i.e. economic integration) but encountered impermeable barriers if it tried to spill over to questions affecting key national interests (Hoffmann, 1966). The same was true for supranational institutions. Member States still considered some (high policy) areas like foreign policy to be theirs. If supranational institutions were seen to infringe on those, they would not hesitate to curtail their competencies.

The basic point intergovernmentalists made was that European Integration tended to flourish where positive outcomes for all involved could be guaranteed (the Common Market serves as the foremost example in this context), but would stall once the national interests of one or more countries directly contravened those of others (as during the Empty Chair Crisis, French veto of UK accession, etc.).

Intergovernmentalism reached its prime in the ‘doldrum years’ of European Integation (Wiener & Diez, 2009: 6) during the 1970s, when the failure to get any further with political integration seemed to confirm most of its premises. Yet, like neo-functionalism, intergovernmentalism was quickly met by events that did not fit its theoretical framework. The signing of first the Single European Act (1986) and subsequently the Maastricht Treaty (1991) asked serious questions of the dichotomy between low and high politics at intergovernmentalism’s core. How, for example, was it possible that, with the creation of the European Monetary Union and the European Common Foreign and Security Policy, states ‘willingly surrendered control over issues of central importance to national sovereignty’ (Rosamond, 2000, p. 79)?

Transfer of loyalty? Margaret Thatcher may have been campaigning to keep Britain within the European Economic Community in the 1970s, but her hawkish line whilst in office during the 1980s has made her into the darling of many an intergovernmentalist.

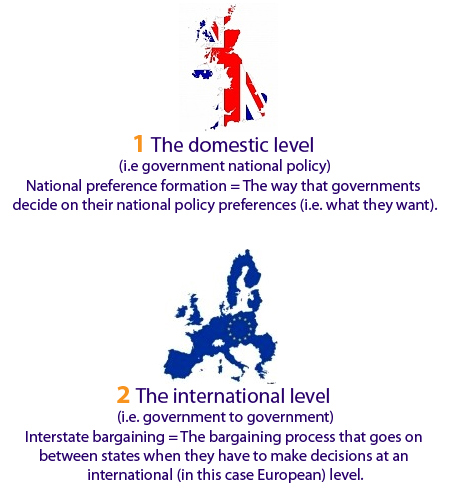

Faced with this conundrum and even with a resurgent neo-functionalism, Andrew Moravcsik undertook to adapt intergovernmentalism to the new European reality of the 1990s. In his efforts to explain European Integration ‘from Messina to Maastricht’ (1998), he devised the concept of ‘liberal intergovernmentalism’. This differed from classic intergovernmentalism in that it emphasised domestic rather than national interests. First, on the domestic level, various interest groups would compete in order to influence national preference formation in integration. Then, the outcomes of these struggles would go on to inform the positions taken by governments in interstate bargaining.

Let’s break that down. . .

Finally, if governments feared the resultant agreement was not going to be lived up to by the other parties, they would favour the transfer of sovereignty to supranational institutions better placed to force compliance (Schimmelfennig, 2004).

Let’s take an example in order to understand this process better.

- The agricultural sector is an important interest group in France, with a high potential for influence at the governmental level.

- They managed to influence the national preference of France regarding the sector at the EU level, favouring the creation of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). This would enable French agricultural surpluses to be exported in a liberalised market.

- The transfer to a supranational institution is exemplified by the French government pushing for a highly centralised CAP, in order to ensure compliance by other members.

But the position of states vis-à-vis supranational institutions always remained strong, as interstate bargaining occurs in a situation where government leaders often know more about each other’s preferences than the out-of-touch supranational institutions.

Like neo-functionalism, liberal intergovernmentalism (LI) has faced critique. For some of the criticisms levelled against Moravcsik, see Schimmelfennig (2004: 81-83). Some scholars have taken issue with the predominant focus on states within LI and its concentration only on the domestic and interstate levels.

Indeed, as will be discussed in the following extract, some scholars have asserted that attention should be maintained on the supranational and transnational levels, factors that LI largely downplays.

Click here to read an extract on liberal intergovernmentalism.

- Notice the ‘two levels games’ of LI and the merge of two different theories at the domestic and international levels?

- Notice the critiques of the theory?

- What do you think – does LI account for European integration more effectively than neo-functionalism?

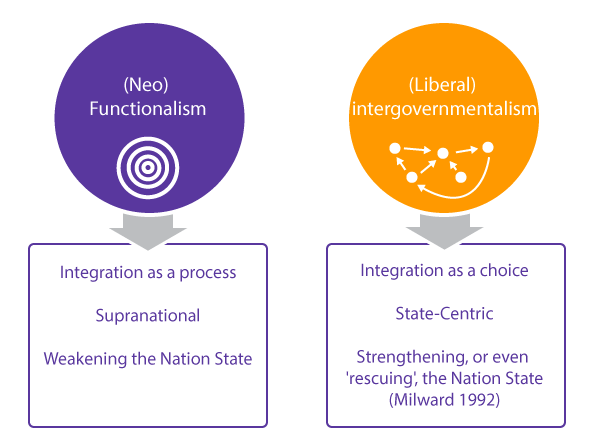

Despite all their undoubted shortcomings, (neo)functionalism and (liberal) intergovernmentalism are still the two absolute classics of European Integration Theory. Even though both theories have over time co-opted bits and pieces of each other, they provide conflicting accounts of how European Integration comes about and works. Here is a table to recall the main differences between those two theories:

Perhaps the best way to understand the manifold debates between (neo)functionalists and (liberal) intergovernmentalists is to notice that they are at their best when describing different things: where (liberal) intergovernmentalism seems to capture the dynamics of ‘big’ treaty negotiations aptly, (neo)functionalism is better suited to cover the day-to-day workings of the European Union.

Calendar

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

| 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | |

Leave a Reply